Perceptions of the Impact of Exclusionary Disciplinary Consequences on Ninth Grade, Black Students’ Mathematics Achievement: A Phenomenological Study

Megan Jones

Sam Houston State University

Abstract

The researcher interviewed two Algebra I teachers in an east Texas, urbanesque high school regarding their perceptions of the impact of exclusionary disciplinary consequences on ninth grade, Black students mathematics achievement. Historically, minority students have been overrepresented in the receipt of exclusionary disciplinary actions, such as in-school suspensions, suspensions, placement in disciplinary alternative education programs, and expulsions. Interviewees revealed that few students exhibited negative behaviors and that exclusionary consequences impacted mathematics achievement, more so than other subjects, because math is reliant upon scaffolding. Possible reasons for teacher perceptions, and greater interview details, are discussed in this study.

Keywords: exclusionary disciplinary consequences, mathematics achievement

In August 2008, the United States Census Bureau released resident population projections by race and Hispanic origin status for 2010 and 2015. The U.S. Census Bureau (2008) projected the number of school age children (five to 19) in 2010 to be 63,051,000. Race and ethnic division of the 63,051,000 children projected in 2010 was 48,018,000 White individuals of school age; 9,442,000 Black individuals of school age; 776,000 American Indian/Alaska Native individuals of school age; 2,753 Asian individuals of school age; and 142,000 Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander individuals of school age (U.S. Census Bureau, 2008).

Each group, racial, ethnic, and total population, increased in number in the United States Census Bureau’s 2015 projection (2008). Such immense diversity in United States public schools creates a great diversity of issues that have historically been addressed through legislation advocating equitable and safe education (Alexander & Alexander, 2009). The researcher included the review of literature that follows in order to provide a historical overview of exclusionary discipline in public schools, and how such exclusionary consequences have a greater impact on minority student achievement due to assignment inequity.

Review of the Literature

Prior to the era of equity in public education advocated today, the United States operated under a “separate-but-equal” (Alexander & Alexander, 2009, p. 1019) doctrine, a result of the Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) court case (Alexander & Alexander, 2009). Initially, cases such as Brown v. Board of Education (1954) and legislation such as the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Title IX amendment (1972) addressed the necessity for equity in education (Alexander & Alexander, 2009; Rist, 1979; Streitmatter, 1986). Streitmatter (1986) elaborated, “In the years following Brown, increasing support of the notion of egalitarianism in the schools has been illustrated through legislation and litigation favoring sex equity, school integration, bilingual and multicultural education, special education, and due process for all students” (p. 139).

Laws advocating equitable education were joined by laws that attempted to protect the safety and well being of children while at school (Alexander & Alexander, 2009). After addressing equitable education, legislation such as the Gun-Free Schools Zone Act (1990), the Safe Schools Act (1994), and the Safe and Drug-Free School and Communities Act (1994) were passed to address the growing concerns over violence, drugs, and weapons in United States’ public schools (Casella, 2003; Skiba, 2000). In addition to new legislation, the 2004 amendments to the Individuals with Disabilities Act aligned special education policy with that of general education, leading both in the direction of zero tolerance for instances of student misbehavior (Skiba, 2000).

Zero Tolerance

By definition, zero tolerance is “a school or district policy that mandates predetermined consequences or punishments for specific offenses” (U.S. Department of Education, 1998, p. 18). However, the policy did not begin in public schools. “Zero tolerance first received national attention as the title of a program developed in 1986 by U.S. Attorney Peter Nunez in San Diego, impounding seagoing vessels carrying any amount of drugs” (Skiba, 2000, p. 4). This no-nonsense approach sent a harsh message to offenders that their illegal actions or behaviors would not be tolerated. Originally in the realm of drug trafficking, zero tolerance spread “to issues as diverse as environmental pollution, trespassing, skate boarding, racial intolerance, homelessness, sexual harassment, and boom boxes” (Skiba & Peterson, 1999, p. 373). Sought in zero tolerance policies are the implementations of the harshest possible punishments on offenders to deter the likelihood of those offenses occurring again.

Adoption of zero tolerance policies in schools was not supported by all administrators, teachers, parents, students, or community members (Gordon, Piana, & Keleher, 2000). Citizens in opposition to zero tolerance argued that the policy was too harsh for enforcement in public schools, because seemingly trivial actions were being handled with the full force of the law (Gordon et al., 2000). Politically, constituents complained that manpower and money were being wasted; whereas publicly, school stakeholders felt administrators and teachers were being forced to implement consequences that may not be the most effective for the student offender in question (Gordon et al., 2000). For example, instances of student expulsions for “paper clips to minor fighting to organic cough drops” (Skiba, 2000, p. 5) led to the negative dialogue that surrounded zero tolerance (Skiba, 2000).

Discipline in Schools

Zero tolerance impacted public education discipline practices, but public schools continued to utilize a variety of disciplinary consequences to meet the needs of their diverse populations (Texas Education Agency, 2010b). In-school suspension (ISS) is the lowest level exclusionary consequence a student can receive (Texas Education Agency, 2010b). Researchers defined ISS as the removal of a student from the classroom, not the school grounds, to facilitate continued instruction (Costenbader & Markson, 1998). Costenbader and Markson (1998) compared ISS to a timeout, however, ISS programs serve many students simultaneously, and therefore ISS programs may be observed as a group timeout to an outsider. Suspension is the next level of disciplinary action (Texas Education Agency, 2010b). “Suspension refers to an out-of-school suspension, during which a student is excluded from school for disciplinary reasons for [one] school day or longer” (U.S. Department of Education, 2009b, p. 1). Placement in a disciplinary alternative education program (DAEP) is the third level of discipline a student can receive for misbehavior (Texas Education Agency, 2010a). A DAEP functions as a regular school environment, but may or may not be located away from the school property.

Student placement in a DAEP may be mandatory or discretionary depending upon campus and district policy (Texas Education Agency, 2010a). Finally, the most severe disciplinary consequence is expulsion (Texas Education Agency, 2010b). Expulsion is the required or discretionary removal of a student from school for the commitment of an extreme offense (e.g., aggravated assault on a student or staff member; used, displayed, or possessed a firearm; arson; a felony offense involving alcohol or a controlled substance) (Texas Education Agency, 2007). Expulsion, along with the other exclusionary disciplinary practices, operated under the assumption that removing a dangerous or an excessively or persistently disruptive student should increase the safety and effectiveness of the learning environment for those students that remain (Brownstein, 2010).

Equity of Disciplinary Consequences

Providing a safe and effective learning environment led to the widespread adoption of zero tolerance policies and the use of exclusionary discipline methods. Zero tolerance and exclusionary disciplinary consequences have impacted all students, but most strongly impacted are minority students (Krezmien, et al., 2006). Inadequate professional development, lack of proper classroom management, and failure to try methods of positive behavior interventions could be to blame for the stark impact of zero tolerance, particularly for minority students (Costenbader & Markson, 1998; Peterson, 2005). “In Massachusetts during the 2000-2001 school year, Rabrenovic and Levin (2003) found that although Hispanic and African American students comprised only 19.4% of the public school student population, they represented 56.7% of school exclusions” (Krezmien et al., 2006, pp. 217-218). This trend of minority overrepresentation was not only evidenced in Massachusetts, but also nationwide. Brownstein (2010) stated that from 1974 through 2006 the instances of student suspensions or expulsions (i.e., exclusions) had nearly doubled.

In addition to disciplinary inequity, researchers hypothesized a “domino effect that further widens the achievement gap” (Townsend, 2000, p. 381). Townsend (2000) explained that school staff was prone to have lower expectations or more remedial objectives for students who have received exclusionary disciplinary consequences. “Students with histories of school exclusion may be subjected to lower-track or remedial programming. If that programming is not effective, those students may continue to receive poor academic grades and be retained more frequently than other students” (Townsend, 2000, p. 382). Placing focus on the achievement gap, Gregory and colleagues (2010) cited other studies (e.g., Nichols, 2004; Skiba, 2000) mentioned to show the disproportionate number of minority students receiving exclusionary disciplinary consequences. Excluding students negatively impacts their level of learning and has not been shown to prevent a second, or third, offense. Researchers (e.g., Gregory et al., 2010; Kralevich et al., 2010) have documented a correlation between minority student exclusionary discipline practice and the achievement gap.

Furthermore, researchers mentioned the increased expectations and demands placed on teachers as one possible explanation of disciplinary inequity affecting student achievement. Teachers were expected to manage their classrooms effectively, however, Kralevich and colleagues (2010) elaborated as follows with regard to classroom management, removal, and achievement:In the event of student misbehavior, an appropriate consequence is assigned to combat the inappropriate conduct. As the degree or frequency of the undesired conduct increases, the severity of the behavior intervention escalates. Historically, combating student misconduct has resulted in punitive measures that remove the student from the regular education setting. (p. 2) “The suspended student is estranged from the school setting and academic instructional time is lost” (Costenbader & Markson, 1998, p. 61). Loss of instructional time has been documented to increase the achievement gap between majority students and minority students, and does not provide an opportunity for students to reform their behavior (Foney & Cunningham, 2002; Morrison & Skiba, 2001; Nichols, 2004; Sullivan, 1989; Tobin & Sugai, 1999). Nichols (2004) indicated the adverse effects of repetitive disciplinary issues for minority students as (a) continued academic disengagement; (b) a widened achievement gap between minority and majority students; (c) a negative point of view towards educational institutions, instructors, and expectations; and (d) eventual academic failure.

Summary of the Literature

Overall, disciplinary consequences in the public school system are issued to minority students (i.e., Black or African American, American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, or Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander) more often than their majority (i.e., White) peers. Review of literature on the topic of disciplinary consequences consistently demonstrated a higher rate of minority students being assigned to ISS, to OSS, to placement in a DAEP, or the most severe, to expulsion. Researchers’ explanations for inequities varied from cultural misunderstandings to school- or community-related issues.

Regardless of the cause, consistent assignment of minority students to exclusionary disciplinary consequences has not terminated the undesired behaviors and continues to negatively impact minority students, both socially and academically, by way of loss of instructional time. Educational leaders are accountable for the learning of all students (Noguera, 2003), thus, inequitable assignment of exclusionary discipline consequences, the negative impact exclusionary consequences have on students, and possible solutions to inequitable assignment of exclusionary disciplinary consequences have become imperative for further study.

Statement of the Problem

Great diversity in the U.S. public education system has led to disciplinary turmoil, inequitable disciplinary practices, and concern about student achievement. Researchers, Krezmien, Leone, & Achilles (2006), indicated that inequitable disciplinary consequences are issued more often to racial and ethnic minorities than to their minority counterparts. An abundance of research suggested that more instances of in-school suspension, out of school suspension, disciplinary alternative education placement, and expulsion have increased the achievement gap (Gregory, Skiba, & Noguera, 2010). The predominant minority student groups identified are Black or Hispanic students in this research. Researchers (Gregory et al., 2010; Kralevich, Slate, Tejeda-Delgado, & Kelsey, 2010; Skiba, 2000) have documented the negative impact exclusionary discipline has on all students, but as minority students are receiving more instances of exclusion, the impact on their achievement is greater (Skiba, 2000). Loss of instructional time is detrimental to student performance on assessments at the

local and state levels, and educational equivalents provided to students while in an exclusionary setting are not equal to in-class instruction (Skiba, 2000). Several studies have examined the effects of inequitable exclusionary disciplinary practices on middle school students in the state of Texas and explained the negative impacts on seventh and eighth grade student achievement (Kralevich et al., 2010). A major challenge for educators and researchers is to examine the impact of inequitable exclusionary discipline practices on student achievement at the secondary level, to explore the causes of such inequities, and to provide viable solutions to the problem. Ninth grade is a crucial grade level to investigate due to its importance and priority in transitioning from eighth to ninth grade mathematics. Thus, further research is needed regarding the relationships between exclusionary discipline, ethnicity, and mathematic achievement at the ninth grade level.

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this study is to identify the perceptions of two Algebra I teachers in terms of the impact exclusionary disciplinary consequences have on ninth grade, Black students’ mathematics achievement. Both teachers, one in an Algebra I co-teach class and the other in an Algebra I sheltered instruction class, work in a 9-12th grade urbanesque high school with an approximate total student population of 2,600 students. This researcher will use data from the Academic Excellence Indicator System (AEIS) and interviews conducted with the teachers to explore exclusionary

disciplinary consequences in relationship to mathematic achievement of ninth grade Black students. Exclusionary discipline data (e.g., referrals) was used to determine the number of in-school suspensions, out of school suspensions, and disciplinary alternative education program (DAEP) placements. AEIS data was used to determine ninth grade student achievement in mathematics. Faculty interviews provided insight into the reasons for possible inequitable assignment of exclusionary disciplinary consequences.

Theoretical Framework

An examination of the relationship between exclusionary disciplinary consequences, ethnicity, and student achievement will be conducted using the equity theory. Adams, a workplace and behavioral psychologist, developed his Equity Theory in 1962 (Leventhal, 1976). “According to the theory, human beings believe that rewards and punishments should be distributed in accordance with recipients inputs or contributions” (Adams, 1963, 1965; Homans, 1974; Leventhal, 1976, p. 3). Further research was

conducted to determine the fairness of reward and punishment distribution, as well as the impact that violating norms of equitable distribution had on participants. In education, and for the purposes of this examination, educators may apply Adam’s Equity Theory in adherence to the belief that a student’s contribution to the learning environment, and that alone, should determine the distribution of rewards or punishments.

Research Questions

The following research questions were addressed in this study:

- What are the perceptions of Algebra I teachers regarding the behaviors of ninth grade, Black students, that lead to enforcement of exclusionary disciplinary consequences in one east Texas urbanesque high school?

- How do exclusionary disciplinary consequences affect 9th grade Black students’ mathematics achievement in one east Texas urbanesque high school?

Methodology

Introduction

To address the research question in this study, a qualitative research design will be used. Johnson and Christensen (2008) explained that qualitative research relies heavily on nonnumerical data, gathered through observations, surveys, or interview questions. “Qualitative researchers prefer to study the world as it naturally occurs, without manipulating it (as in experimental research)” (Johnson & Christensen, 2008, p. 388). One method of qualitative research, utilized for the execution of this study, was phenomenological research (Creswell, 2007). Creswell (2007) explained that a phenomenological study consisted of the following: (a) Multiple individuals, who have experienced the same phenomenon, are participants in the study; (b) Study participants are purposefully selected based on their experience and typically are interviewed by the researcher to understand the phenomenon; and, (c) Multiple interviews may be necessary for the researcher to fully understand the participants’ experience. The purpose of this study is to identify the perceptions of two Algebra I teachers regarding exclusionary disciplinary consequences’ impact on ninth grade, Black students’ mathematics achievement, thus interviews of more than one teacher who has experienced the phenomenon of teaching students who have received exclusionary disciplinary consequences meets the criteria of a phenomenological study (Creswell, 2007; Johnson & Christensen, 2008).

Participants

Participants in this study were two Algebra I teachers in an urbanesque Texas high

school. Both teachers were White females teaching ninth grade Algebra I students. Teacher A has a combination of Algebra I on level and Algebra I co-teach classes, while Teacher B has a combination of Algebra I on level and Algebra I sheltered instruction classes. Further teacher statistics are provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Teacher Statistics and Information

|

Teacher Information |

Teacher A |

Teacher B |

|

Years of Total Teaching Experience |

9 |

16 |

|

Years at Current High School |

4 |

7 |

|

Students Per Period |

24 |

20 |

|

Previous Grade Levels Taught |

6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, and 12 |

6, 7, 8, 9, and 10 |

|

Previous Subjects Taught |

Grades 6, 7, and 8 Math Geometry; Algebra 2; Math Models; Pre-Calculus; and, |

Grades 6, 7, and 8 Math; and, Geometry |

Teacher A and Teacher B were purposefully selected to participate in this study because of their experience in teaching classes with a high minority student population, their experience with classroom management, and their anticipated candor in discussing their views and perceptions of exclusionary disciplinary consequences’ impact on ninth grade, Black students’ mathematics achievement.

Context of the Study

One action-researcher was associated with this study. The researcher decided to identify teachers’ perceptions of exclusionary disciplinary consequences’ impact on ninth grade, Black students’ mathematics achievement due to the following: (a) Of the ninth grade students tested, 68% met the expectations on the 2009-2010 Texas Assessment of Knowledge and Skills (TAKS) test; (b) The lowest scoring sub population on the ninth grade 2009-2010 TAKS mathematics test were Black students, with 53% meeting the expectations; (c) Ninth grade, Blacks students’ who met the expectations in 2008-2009 were 56%, and that percentage dropped to 53% in 2009-2010; (d) Ninth grade mathematics was the lowest performing state assessed area campus wide; and lastly, (e) Ninth grade mathematics at the campus involved in the study was four percentage points below the state of Texas average (Texas Education Agency, 2010c).

The researcher acknowledges that personal bias may have affected the collection of data. Johnson and Christensen (2008) explained, “It is true that the problem of researcher bias is frequently an issue in qualitative research because qualitative research tends to be exploratory and is open-ended and less structured than quantitative research” (p. 275). To address possible researcher bias, interview questions were reviewed and feedback provided, the researcher reflected on the course of the interview, and the interviewer engaged in peer review of interview transcripts (Johnson & Christensen, 2008).

Data Collection and Data Analysis

Data was collected using a qualitative approach that consisted of “open-ended questions” (Johnson & Christensen, 2008, p. 207) that allowed the researcher to obtain “in-depth information about a participant’s thoughts, beliefs, knowledge, reasoning, motivations, and feelings about a topic” (Johnson & Christensen, 2008, p. 207). Interviews occurred in a one-on-one setting with the teacher and the researcher. Teachers were asked several open-ended questions about their beliefs and observations of ninth grade, Black students’ receipt of exclusionary disciplinary consequences and the behaviors associated with those consequences. After the interview process, the researcher analyzed data by categorizing responses into categories of common themes. Upon establishment of common themes, a second interview was conducted in a one-on-one setting with the teacher and the researcher to clarify and elaborate on responses received in the first interview. The researcher took detailed notes during all interviews and participants reviewed the researchers transcripts to establish validity.

Limitations

The credibility and validity of this study may have been impacted by one or more of the following limitations. First, researcher bias existed as the researcher was a native in the east Texas urbanesque high school. The researcher has worked extensively with Teacher A and Teacher B, thus, interpretive validity may have been threatened due to the researcher’s beliefs, opinions, or preconceived ideas of the interviewees’ possible responses. Furthermore, interview responses may not be generalized to other locations or subject areas at this time. Temporal credibility was a limitation to this study as Teacher A and Teacher B were interviewed on different dates and at different times during the day. Lastly, the effect size of two may not be sufficient to draw widespread conclusions regarding the perceptions of exclusionary disciplinary consequences’ impact on ninth grade, Black students’ mathematics achievement (Leech & Onwuegbuzie, 2007; Onwuegbuzie & Leech, 2006).

Results and Discussion

Researchers (Costenbader & Markson, 1998; Gregory et al., 2010; Skiba, 2000) determined that exclusionary disciplinary consequences negatively impacts the achievement of all students, however, the discrepancy of minority students receiving a greater number of exclusionary placements serves to further widen the achievement gap. Leventhal’s (1976) Equity Theory explained that the human being assumes rewards and punishments are distributed in response to an individual's contribution, whether positive or negative, to a situation.

Inequitable assignments of exclusionary disciplinary consequences are academically detrimental to minority students, and furthermore, have the potential to increase the likelihood of detrimental consequences later in life (e.g., sustained achievement gap; educational disengagement; negative perspective toward the educational institution, instructors, and values; and, increased likelihood of incarceration) (Nichols, 2004).

Question 1 Themes

In response to the first research question, two themes emerged in terms of teacher perceptions. Research question one stated, “What are the perceptions of Algebra I teachers regarding the behaviors of ninth grade, Black students, that lead to enforcement of exclusionary disciplinary consequences in one east Texas urbanesque high school?” An interview question that sought to understand the behaviors of students in Algebra I stated, “How would you describe the behavior of 50%, 25%, 10% of the students in your class?” Responses to this question led to the development of the first theme: Negative behaviors exhibited by few. Teacher A responded that 50% of students do a good job, 25%’s performance is dependent upon mood, and 10% behave as if everyday is the first or second day of school. Teacher B concurred that 50% truly want to be in school and demonstrate a strong work ethic, 25% do not enjoy math but they try to learn the material, and 10% do not care. Teacher B did state that another 10% of students are exceptional.

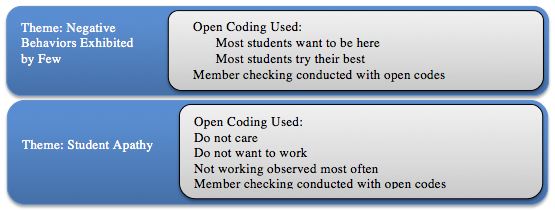

The second theme that emerged in correlation to the first research question was student apathy. Both Teacher A and Teacher B reported the most frequently observed undesirable behaviors as not trying to be successful and not working on assignments in any capacity. Teacher A elaborated that students not working on assignments was complicated by students talking during direct instruction, thus falling further behind due to lack of understanding. Both teachers were inherently positive, despite this observation, and explained that they each have high expectations for students’ success and they were not willing to lower their academic or behavioral expectations for approximately 10% of their populations. Figure 1 provides open coding and emergent themes from the coding.

Figure 1. Research Question 1 Open Coding and Themes

Question 2 Themes

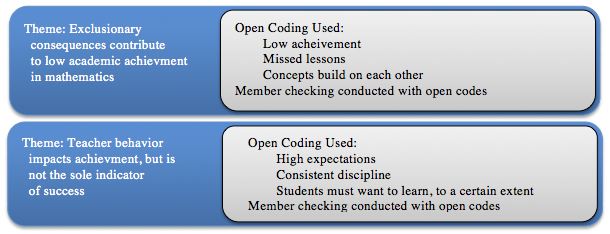

In response to the second research question, two themes emerged in terms of teacher perceptions. Research question two stated, “How do exclusionary disciplinary consequences affect 9th grade Black students’ mathematics achievement in one east Texas urbanesque high school?” Responses to several interview questions led to the emergence of theme one: Exclusionary consequences contribute to low academic achievement in mathematics. Teacher B explained that Black females posed the greatest disruption in the classroom and because of their disruptive behavior, they failed to learn the curriculum, and when they were punished for the disruptive behavior, they were removed from class, again creating a situation where they failed to learn the curriculum. Teacher A agreed and elaborated that not only does the behavior in class negatively affect the student doing it, but other students may be distracted by the noncompliant behavior and also suffer lower academic achievement as a result.

Furthermore, mathematics is a subject particularly sensitive to the scaffolding of concepts. If a student is not present for the beginning of a unit, the likelihood he or she will grasp the overall concept is minute. In further discussion, the second theme developed: Teacher behavior impacts achievement, but is not the sole indicator of success. Teacher A discussed her experience with diverse student populations, at length, and Teacher B worked with great success at a DAEP in the same district as the urbanesque east Texas school in this study. Both teachers have undergone extensive professional development regarding discipline, diversity, and dealing with students from poverty. Such experience makes both teachers ideal in working with minority student populations, however, each teacher still acknowledged Black students’ mathematics achievement suffering due to imposement of exclusionary discipline. Figure 2 provides open coding and emergent themes from the coding.

Figure 2. Research Question 2 Open Coding and Themes

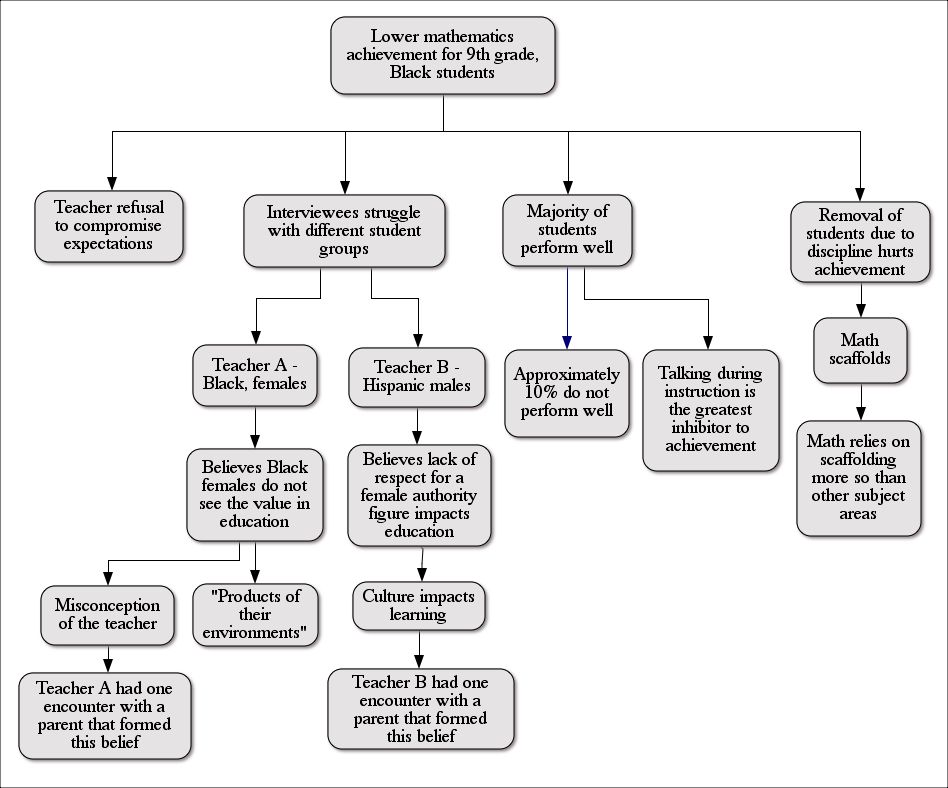

A difference in perspective emerged between Teacher A and Teacher B when asked about the reasons for classroom disruption and subsequent exclusionary consequences. Teacher A believed that classroom disruption emerged from Black females’ misconceptions about the classroom and classroom expectations. Teacher A explained that these misconceptions seemed valid based on past conferences with parents of Black females who did not value education and had not instilled a value for education in their children. In contrast, Teacher B struggled more with Hispanic males, not Black students as were the focus of this study.

Teacher B speculated that struggles with Hispanic males compliance stemmed from cultural beliefs that men were superior to women; thus, a Hispanic male student did not readily follow the directions of a female teacher. Furthermore, Teacher B was in a co-teach classroom, with a male co-teacher, who did not experience the same difficulty with Hispanic males, thus the basis for Teacher B’s assumption. Figure 3 provides an overview of interview results, including differences in perceptions that the researcher did not anticipate.

Figure 3. Teacher Perceptions

Conclusion

Consequences issued to ninth grade Black students, in particular, are perceived by two Algebra I teachers in an urbanesque east Texas town to lower mathematics achievement, and as researchers (Costenbader & Markson, 1998; Gregory et al., 2010; Nichols, 2004; Skiba, 2000) stated, widen the achievement gap. The majority of students sought to perform at the highest possible level, both academically and behaviorally, but a small, approximated percentage demonstrated great apathy. Sullivan (1989) posited how exclusionary placements may provide academically sound instruction to students

who have been placed there, but currently exclusionary programs are not adequate as evidenced by low achievement for students who are suspended or have been given a DAEP placement. Further research is recommended on how to develop and successfully implement character education programs to address behavior, or how to develop and successfully sustain an exclusionary disciplinary system that addresses inequitable disciplinary assignments and the academic needs of students, particularly ninth grade, Black students as this is a crucial area affecting secondary student success.

References

Adams, J.S. (1963). Toward an understanding of equity theory. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 67, 422-436.

Adams, J.S. (1965). Inequity and social exchange. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in Experimental social psychology, 2. New York, NY: Academic Press, 267-299.

Alexander, K., & Alexander, M. D. (2009). American public school law. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage Learning.

Casella, R. (2003). Zero tolerance policy in schools: Rationale, consequences, and alternatives. Teachers College Record, 105(5), 872-892.

Costenbader, V., & Markson, S. (1998). School suspension: A study of secondary school students. Journal of School Psychology, 36(1), 59-82. doi:10.1016/S0022-4405(97)00050-2

Creswell, J. W. (2007). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Foney, D. M., & Cunningham, M. (2002). Why do good kids do bad things? Considering multiple contexts in the study of antisocial fighting behaviors in African American urban youth. The Journal of Negro Education, 71(3), 143-157.

Gordon, R., Piana, L. D., & Keleher, T. (2000). Facing the consequences: An examination of racial discrimination in U.S. public schools. (ERASE Initiative Reports-Descriptive 141). Retrieved from ERASE Initiative Applied Research Center website: http://www.arc.org

Gregory, A., Skiba, R. J., & Noguera, P. A. (2010). The achievement gap and the discipline gap: 2 sides of the same coin? Educational Researcher, 39(1), 59-68. doi:10.3102/0013189X09357621

Hochschild, J. L., & Scovronick, N. B. (2003). The American dream and the public schools. New York, NY:

Oxford University Press.

Houle, C. O. (1974). The changing goals of education in the perspective of lifelong learning. International Review of Education, 20(4), 430-446. doi:10.1007/BF00598239

Johnson, B., & Christensen, L. (2008). Educational research: Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed approaches.

Thousand Oaks: CA, Sage.

Kralevich, M., Slate, J. R., Tejeda-Delgado, C., & Kelsey, C. (2010). Disciplinary methods and student achievement: A statewide study of middle school students. International Journal of Educational Leadership Preparation, 5(1), 1-20.

Krezmien, M. P., Leone, P. E., & Achilles, G. M. (2006). Suspension, race, and disability: Analysis of statewide practices and reporting. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 14(4), 217-226. doi:10.1177/10634266060140040501

Leech, N. L., & Onwuegbuze, A. J. (2007). An array of qualitative data analysis tools: A call for data analysis triangulation. School Psychology Quarterly, 22(4), 557-584. doi: 10.1037/1045-3830.22.4.557

Leventhal, G. (1976). What should be done with equity theory? New approaches to the study of fairness in social relationships. Retrieved from http://www.eric.ed.gov/ERICWebPortal/search/detailmini.jsp?_nfpb=

true&_&ERICExtSearch_SearchValue_0=ED142463&ERICExtSearch_ SearchType_0=no&accno=ED142463

Nichols, J. D. (2004). An exploration of discipline and suspension data. The Journal of Negro Education, 73(4), 408-423.

Onwuegbuzie, A. J., & Leech, N. L. (2006). Validity and qualitative research: An oxymoron?. Quality & Quantity, 41, 233 -249.doi: 10.1007/s11135-006-9000-3

Public Law 103-227. (1994). Gun-Free Schools Act. SEC 1031, 20 USC 2701.

Public Law 103-227. (1994). Safe Schools Act. SEC 701, 20 USC 5961.

Public Law 103-382. (1994). Safe and Drug-Free Schools and Communities Act. SEC 4001, 20 USC 7101.

Rabrenovic, G., & Leven, J. (2003, May). The quality of post exclusion assignments: Racial and ethnic differences in post exclusion assignments for students in Massachusetts. Paper presented at the School to Prison Pipeline Conference, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.

Rist, R. (1979). Desegregated schools: Appraisals of American experiment. New York, NY: Academic Press.

Scheurich, J. J., & Skrla, L. (2003). Leadership for equity and excellence [Adobe Digital Editions version]. Retrieved from http://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=PrSbPPiH-

&oi=fnd&pg=PR9&dq=disciplinary+equity%2

Bachievement+gap&ots=ewsmjkHntf&sig=a0amyN1ASq2YneKy_SP3ii7BTyw#v=onepage&q&f=false

Skiba, R. J. (2000). Zero tolerance zero evidence: An analysis of school disciplinary practice. Indiana Education Policy Center, Policy Research Report #SRS2. Retrieved from http://www.indiana.edu/~safeschl/ztze.pdf

Streitmatter, J. L. (1986). Ethnic/racial and gender equity in school suspensions. The High School Journal, 69(2),139-143.

Sullivan, J. S. (1989). Elements of a successful in-school suspension program. NASSP Bulletin, 73(516), 33-38.

doi:10.1177/019263658907351607

Swadi, H. (1992). Relative risk factors in detecting adolescent drug use. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 29(3), 253-254.

Texas Education Agency. (2007). 2006-2007 Methodology for identification of campuses: Required to implement the school safety choice option. Retrieved from http://ritter.tea.state.tx.us/nclb/PDF/SSCOMethodology2006-07.pdf

Texas Education Agency. (2010a). Standards for the operation of school district disciplinary alternative education programs. Retrieved from http://ritter.tea.state.tx.us/rules/tac/chapter103/ch103cc.html

Texas Education Agency. (2010b). Education Code 37. Alternative settings for behavior management. Retrieved from http://www.statutes.legis.state.tx.us/Docs/ED/htm/ED.37.htm

Texas Education Agency. (2010c). Academic Excellence Indicator System 2009-2010 Campus Performance:

Bryan ISD, Bryan High School. Retrieved from http://ritter.tea.state.tx.us/cgi/sas/broker

Townsend, B. L. (2000). The disproportionate discipline of African American learners: Reducing school suspensions and expulsions. Exceptional Children, 66(3), 381-391. United States Census Bureau. (2008). 2006-2008 American community survey 3-year estimates [Data file]. Retrieved from http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/DTTable?_bm=y&-geo_id=01000US&ds_name=ACS_2008_3YR_G00_&-redoLog=false& mt_name=ACS_2008_3YR_G2000_B02001

United States Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. (1998).

Violence and discipline problems in U S. public schools: 1996-97. NCES 98-030 by S. Heaviside, C. Rowand, C. Williams, and E. Farris. Project Officers, S. Burns and E. McArthur. Washington, DC: Author.

United States Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics and Institute of Education Sciences. (2009). Table A-28-1: Number and percentage of students who were suspended and expelled from public elementary and secondary schools [Data file]. Retrieved from http://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/2009/section4/table-sdi-1.asp

Megan Jones is a TAP Master Teacher at Bryan High School. Prior to this, Megan taught eighth through twelfth grade English at Calvert Jr./Sr. High School and at Bryan High School. She received her Bachelors of Arts (English) from Texas A&M University, her Masters in Educational Administration from Sam Houston State University, and is currently working on her Doctorate of Education at Sam Houston State University.

Megan Jones is a TAP Master Teacher at Bryan High School. Prior to this, Megan taught eighth through twelfth grade English at Calvert Jr./Sr. High School and at Bryan High School. She received her Bachelors of Arts (English) from Texas A&M University, her Masters in Educational Administration from Sam Houston State University, and is currently working on her Doctorate of Education at Sam Houston State University.