Today@Sam Article

New Publication Connects SHSU To ‘A Story For The Ages’

June 2, 2015

SHSU Media Contact: Julia May

|

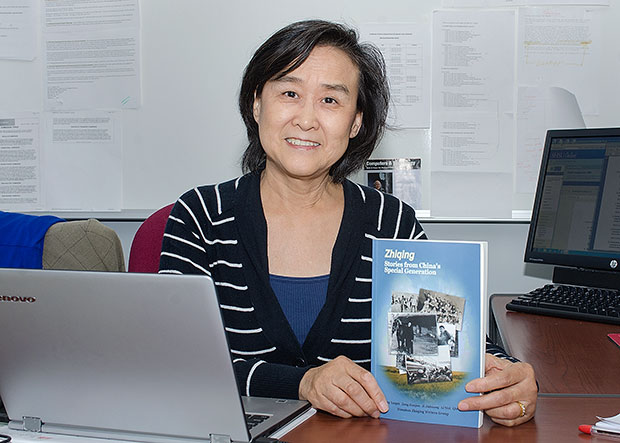

| Computer science professor Ji Jiahuang and many of her contemporaries share their stories of life during China's "Cultural Revolution" in the new Texas Review Press publication "Zhiqing: Stories from China’s Special Generation." —Photo by Brian Blalock |

For Ji Jiahuang, not only is Huntsville, Texas, a world away from the village of Yang in China in distance; but also in comparing her life at the two places, Yang Village might as well be on another planet.

When visiting with Sam Houston State University computer science professor, one might never guess that she lived through one of the darkest times in China’s history.

She is warm, gracious, and politely receptive to questions about her personal experiences during her native country’s “Cultural Revolution,” which took place 40 years ago. Occasionally, you might hear a tinge of sadness in her voice as she discusses her lost youth and that of so many of her peers. However, her enthusiasm quickly returns when she talks about her passion for education and how grateful she is for the opportunity to receive an education, especially at a time when so many like her were denied.

Her story, along with the stories of others like her who now also live the Houston area, have been published by SHSU’s Texas Review Press in the book “Zhiqing: Stories from China’s Special Generation.”

Jiahuang was in the 10th grade in 1966, when China’s Chairman Mao Zedong initiated the Cultural Revolution, a socio-political movement intending to purge what was left of capitalism and tradition and enforce communism. As a result, China’s “lost generation” came into being.

Mao sent all the middle school and high school students from urban areas away from their homes and families into the countryside, where they were to perform manual labor and learn about crops from the peasants. Jiahuang was one of six girls sent to Yang Village.

After a few years of working along side of the peasants, Jiahuang was placed in a “capped” elementary school—an elementary school that offers 6th and 7th grade courses—in the village as a teacher of mathematics and Chinese. Before long, the government started to encourage middle schools to offer English courses. The principal of Jiahuang’s school began a search for an English language teacher.

“I told them I had learned Russian when I was in middle school and high school, and I could teach myself English,” she said. “So I began learning English by getting up at 5 a.m. every day before my workday began to listen to a radio station that taught English.”

Four years after Jiahuang had first been placed in Yang Village, administrators who were in charge of the village schools, came for a site visit. They were so impressed with the way Jiahuang and the other teachers prepared for their classes, they told the young teachers that they might have an opportunity to go to college.

“I was so excited! That was such wonderful news to me,” Jiahuang said. “I filled out the forms, took a variety of examinations, and passed them all. I was then told to wait.”

Out of the 20 young people who were recommended for college, only 10 were selected. Unfortunately for Jiahuang, she was not one of them.

“That year, in 1972, I thought I had missed a once-in-a-lifetime chance and that I would probably stay in the countryside for the rest of my life,” she said.

The following year, the Chinese new leader Deng Xiaoping, who opposed many of Mao’s social and economic theories, began to gain influence. Through his work, universities began to open their doors to more students, although admission was still extremely selective.

“Because I had been a good student in high school, I was highly recommended for college,” Jiahuang said. “It took recommendations in addition to high examination scores to even be considered.”

This time, when she applied, she made the cut and was placed as a student in the mechanical engineering program of Huazhong University of Science and Technology. The program had been chosen for her.

“I was totally surprised,” she said. “I loved mathematics and when I was in the countryside, I taught math and that’s what I wanted my major to be. When I got the admission acceptance letter and learned that I had been designated as a mechanical engineering major, I was frightened because I didn’t feel that was where my talent was.”

The only thing she knew about machinery was from what she had observed in factory tours as a schoolgirl. However, her math skills and her dedication to her studies enabled her to do well in design, and she successfully completed her undergraduate degree in mechanical engineering.

In fact, she had so impressed her professors that when university officials decided to offer a program in the emerging field of computer science, she was tapped to teach in the new program.

Becoming A Computer Scientist

She took a break to get married and have a baby, and then decided to go to graduate school to earn a master’s degree in math. However, she was placed in the computer science program. It did not matter—she was thrilled that she was going back to college. More than 800 students applied, and only 63 were accepted to her university after a three-day, five-subject, highly-competitive examination.

She took a break to get married and have a baby, and then decided to go to graduate school to earn a master’s degree in math. However, she was placed in the computer science program. It did not matter—she was thrilled that she was going back to college. More than 800 students applied, and only 63 were accepted to her university after a three-day, five-subject, highly-competitive examination.

“We were so grateful for the opportunity to advance our education,” she said. “We spent all our time studying. Our teachers were so happy to have us because we were motivated students and so eager to learn. Our library was constantly full of students studying. I remember thinking that the walk from my dormitory to the cafeteria was eight minutes, and I didn’t want to waste those minutes walking when I could be studying!”

She graduated in 1981 with a master’s degree in computer science from Nanjing University.

About that time, the World Bank began lending money to China to send students abroad for education purposes, and Jiahuang was selected to go to the United States. She went to the University of Maryland as a visiting scholar, and once again, she dazzled her teachers with her work ethic and academic ability.

Going To Texas

Austin, Texas, had become attractive to established and start-up tech companies, and the professor with whom she worked decided to move his company there. He invited Jiahuang to go with him, so she then moved to Austin.

Before long, her quest for knowledge pushed her to get a doctoral degree. She applied to the University of Houston, was accepted, and moved in January 1986.

At the beginning of the fall semester that year, representatives from the China Consulate in Education visited the University of Houston and announced that the government was allowing the Chinese students to bring their spouses and children to be with them. By that time, Jiahuang’s husband had earned a master’s degree in electrical engineering in China. At the end of 1986, he and their son joined Jiahuang in Houston.

Jiahuang graduated with her doctorate in computer science in 1990 and was subsequently hired to teach at SHSU, where she has been since.

The year 1998 marked the 30th anniversary of China’s “lost generation” being sent to the countryside, and those who had personally experienced the Cultural Revolution began to talk about a reunion in the villages where they had been. However, it was not feasible for some to leave their jobs to go back for an extended period of time, particularly the ones who now lived in America.

“My husband, Jiahua Yang, who had also been sent to the countryside as a senior in high school, began to talk with our friends in Houston about getting together,” she said. “A date was set for a Houston reunion, and we announced the event in the Chinese newspapers.

“We expected 300 to attend,” she said. “That night, there was a heavy thunderstorm and we thought that the weather might keep people from coming. However, even more than we were expecting came. We were all squeezed together and people did not want to leave.

“Early the next year, the Houston Zhiqing Association was founded, my husband became the first president, and we began to meet regularly and have social events,” she said.

The group started sharing their stories and talked about recording their history, which they did in the book “Three Colored Soil,” written in Chinese.

As businesses and economies became more global in the 21st century, one of our association’s former presidents, Qin Yang, had the idea to jointly write a book in English about life during the zhiqing years, so that western society and their own children would be able to know what they had gone through in the Cultural Revolution.

However, according to Jiahuang, there was a problem.

“English,” she said. “We are not good….”

Networking Through SHSU Connections

That’s how SHSU alumna, Kang Xuepei, became involved. She, too, had been sent to the countryside as a young girl and was now living in Houston. Her journey to Huntsville had been via New Zealand.

“After five years of hard life in the countryside, I attended a teachers’ training course and became a middle school English teacher,” she said. “In 1978, I took the university entrance exam and was admitted to East China Normal University in my home city of Shanghai.”

|

| Jiahuang and the book's other contributors (below) presented their work to members of the the Houston Zhiqing Association earlier this year. Jiahuang and her husband were instrumental in the founding of the association in 1999. —Submitted photos |

|

Upon her graduation, she was assigned to Shanghai University of Science and Technology to teach English.

“To me, it was indeed a dream coming true,” she said. “However, in the early 1980s, China had just opened up and started economic reform. People’s lives were still poor and the housing situation was bad.

Seeking a better life for her family, Xuepei resigned her beloved university teaching job and went to Auckland, New Zealand, because tuition was free there for graduate students. Before long, she was offered a teaching assistantship at SHSU, and completed her graduate work in English.

During her coursework, she served as an intern with Texas Review Press. She wrote a creative writing piece for her master’s thesis, entitled “In The Countryside.”

“It was a simply marvelous collection of essays on Pei’s experiences living among the peasants during China’s Cultural Revolution,” said Paul Ruffin, Texas State University System Regents’ Professor, Distinguished Professor of English at SHSU, and 2009 Texas State Poet Laureate. “I was so impressed by it, that I published the thesis as a monograph. The book was well-received and garnered a few very positive reviews.”

In August 2012, when Qin Yang, called Xuepei and told her his idea about compiling the collection of stories, she opened her old thesis book and started to expand the introduction.

The writers enthusiastically shared their stories and the book began to take shape, even though the process of finalizing the project was sometimes difficult because of all the details.

“It involved much time writing the introduction, preface, editing, and translating the stories,” said Xuepei. “Being self-employed, I was able to devote lots of time to it during the day.”

She also sought the help of her long-time friend, Margaret Slocomb, from Australia, who did the final editing of the stories.

“We didn’t know how to get the book published,” Xuepei said. “However, I thought about Texas Review Press and sent an email of inquiry. To my pleasant surprise, my former professor, Dr. Ruffin, who is the founder and director of Texas Review Press, responded to my email in minutes.”

Since Ruffin was familiar with that period of Chinese history and was confident in Pei’s ability to judge the quality of the writing in the proposed book, he suggested that she send the manuscript to him for consideration.

“After reading over the manuscript, I knew that it was a book that I wanted to publish,” he said.

“It’s not a dry history of that period; it’s an in-depth personal account by a number by these Chinese writers about their travail during this social experiment,” Ruffin said. “No one can tell the story of that period more graphically, more authoritatively, than the people who lived it. The book is a testament to the strength of the human will.”

One thing that surprised Ruffin about the memoirs was the lack of bitterness among the writers.

“They focused on the positive aspects of their experiences and suppressed any inclination to denounce and complain,” he said.

The writers are very happy with the way the book turned out, according to Jiahuang.

“We had a book signing event earlier this year in Houston,” she said. “Of the 13 writers, only four were not able to come, either because they had gone to China or they were working out of town.”

Today, Jiahuang doesn’t dwell on her circumstances nor does she concern herself with what “might have been” if she had been born in a different time. Rather, she celebrates her survival, her determination to get an education, and the results of her hard work in bringing her to the life that she has now.

“Zhiqing: Stories from China’s Special Generation” is available from the Texas A&M University Press Consortium (800.826.8911) or through Amazon.

- END -

This page maintained by SHSU's Communications Office:

Director of Content Communications: Emily Binetti

Communications Manager: Mikah Boyd

Telephone: 936.294.1837

Communications Specialist: Campbell Atkins

Telephone: 936.294.2638

Please send comments, corrections, news tips to Today@Sam.edu